top of page

PRIVATE FRANK NOLAN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNEY THE GREAT WAR MEDICAL SERVICES 1 MEDICAL SERVICES 2 AMBULANCE TRAIN MILITARY HOSPITALS

WAR AND MEDICINE WHEN THEY SOUND THE LAST ALL CLEAR GROUP CAPTAIN DOUGLAS BADER GROUP CAPTAIN DOUGLAS BADER CBE DSO '

THE MEDICAL MEMORIES ROADSHOW

‘To understand where we are today

We have to know where we have come from’

MECHANICAL TREATMENT OF COMAIPOUND

AND SUPPURATING FRACTURES OCCURRING

AT THE SEAT OF WAR.

BY

ROBERT JONES, CH.M., F.R.C.S.ED.

LIVERPOOL.

[WITH SPECIAL PLATE.]

I HAVE been asked to offer some suggestions as to a suitable way of treating certain fractures of the upper and lower limbs as they occur at time seat of war. We realize that wounds as met with during the Boer and Russo-Japanese campaigns were very different in character from those occurring on the richly manured fields in Flanders where suppuration so commonly follows. Time point, therefore, is to decide upon the best way of immobilizing compound fractures in the presence of pus.

The method employed must be both efficient and simple; it must allow easy and painless access to the wound, and protect the Iimb from harm during transport.

From experiences gained by a short visit to the front, and from conversations with many surgeons at home and abroad, I feel strongly that surgeons should abandon all operative methods designed to immobilize the fractured ends. They are fraught with danger and have no place in this campaign.

Plaster-of-Paris, so often used in the treatment of simple fractures, becomes a filthy m-method where suppuration has occurred. Despite every precaution for the exposure of the wound the plaster mops up discharges like blotting paper and becomes horribly offensive adding to the infection of the wound. I would urge my young colleagues at the front to discard it altogether.

FRACTURES OF THE LOWER LIMB.

Hip and Upper Thigh.

Fractures through the hip-joint and those just below the trochanter are best treated by a modification of the Thomas Splint, which I have described as an "abduction frame'" (Fig. 1 a). It is a splint upon which the patient lies and can be carried (Fig. 1 b). Extension is easily maintained and applied, and need not be relaxed for any purpose. The patient is placed upon this splint, and any displacement should be overcome by immediate extension in the abducted plane. The limb should be rotated inwards slightly until the foot is at right angles to the table and be fixed in this position on the frame (Fig. 1 c).

It will be seen by the illustration that both limbs are controlled and that extension is secured by strapping on the injured limb with counter extension by means of a smooth leather groin strap on the opposite side of time pelvis. This groin strap should not be slackened by the nurse under any pretext, but in order to avoid pressure sores she should be instructed to alter the area of skin over the abductors, which is subjected to pressure, by moving to and from. This method of fixed extension in abduction secures the lower limb in relation to time pelvis in a manner which can never be satisfactorily achieved by weight and pulley, where reliance is placed on the weight of the body for counter extension. It is by reflex nervous impulses, induced by changes of tension in the muscle, that muscular spasm is produced. A patient lying in bed with a fractured femur - high up or lower in time shaft-cannot avoid constantly changing the state of tension of the muscles of his thigh if a weight and pulley are attached to his limb. The counterpoise is the weight of his body. Every time he tries to shift the position of his shoulders by digging his elbows into the bed lie alters the tension of his muscles, calling forth a reflex spasm.

When he falls asleep and his muscles relax when he moves in his sleep when he is lifted upon a bedpan or moved slightly by the nurses to have his bed put straight, there is apt to recur this reflex contraction due to sudden change in tension.

The long Liston splint, which is much in use, is quite unsuitable for fractures of the upper thigh. It does not permit abduction but maintains the limb in line with the trunk-a position which must result in angular union.

Furthermore, as the splint extends to tie axilla, any movement of the trunk involves movement of the limb, and attention to the secretions disturbs the fracture.

Both the Liston and the ordinary weight and pulley ace ill-suited for any form of fracture with suppuration, where good alignment, comfort and ease of transport are desired.

The patient who lies on an " abduction frame " can be lifted and moved without pain, without disturbing the fracture or relaxing the extension, and the dressing can be changed without interfering with tile mechanism of fixation. If the wound is through the buttock and the discharge takes places there the splint can be modified as shown in the illustration (Fig. 1 d). The abduction frame can be applied in a few minutes.

Upper Middle and Lower Thigh.

For all other fractures of the thigh, the Thomas Knee splint is incomparably the simplest and best (Fig. 2 a). I have often fixed a fractured thigh in this splint, and sent the patient home in a cab. By reason of its construction, it automatically secures a correct alignment, as any surgeon with a mechanical mind can see if he examines the illustration. I am in the habit of using this splint for the treatment of all fractures of the middle and lover third of the thigh, fractures through the knee-joint, and fractures through the upper and upper middle portion of the leg.

The application of the Thomas bed splint is quite easy. Strapping of adhesive plaster is applied in the

usual way to the sides of the limb. At the lower end of the extension strapping there is a loop of webbing to which is attached a length of strong bandage Fig. 2 b).

The ring of the splint is passed over the foot (Fig. 2 c), and up to the groin till it is firmly against the tuber ischia. The extensions are then pulled tight, the ends turned round. each side bar (Fig. 2 d) and tied together over the bottom end of the splint, which should project 6 or 8 in. beyond the foot. Care must be taken to avoid internal or external rotation of the limb, the foot being, kept at right angles. Local splints can then be employed and are made of block tin or sheet iron. They can be moulded by the hand to fit the limb, and yet, being gutter shaped, they are rigid longitudinally (Fig. 2 e).

They can be disinfected by fire or water. A couple of transverse bandage slings suspend the limb from the side bars of the knee splint. A straight splint is placed behind the suspensory bandages of the thigh and knee.

On the front of the thigh another sheet iron 'splint is applied, and the femur is thus kept rigid (Fig. 2j). The alignment from the hip-joint to the ankle is perfect, being dependent on a straight pull (Fig; -2 g). This splint allows the patient to raise his shoulders, or even sit in bed.

His other leg can be moved freely without altering the tension on his thigh muscles, and--there is no-reflex spasm.

Even if the muscles try to contract, they cannot, for the

ring of the splint is firm against-tie tuber ischia. The

muscles therefore do not remain on the alert but become quiescent and starting pains do not occur. Such is the difference between fixed and intermittent extension

In using this splint little attention is necessary to prevent soreness of the perineum.' The ring of the splint, being covered 'with smooth basil leather, can easily be kept clean, so can the skin. The nurse should also several times a day press down the skin of the buttock and draw a fresh part of the skin -under the splint. To change the point of pressure over the perineum the limb can be elevated or abducted. The dressings can be applied without in any way interfering with the work of the splint. When -the fracture has occurred through the knee or upper tibia the splint is applied in the same way.

It has often been a matter of astonishment to me that the simple an' effective splint has not been universally employed. It can be applied in a few minutes, usually without an anaesthetic, and one is always sure of a good length and good alignment the fractured limb can be moved in any direction without giving pain so that transport is easy and safe. I have never yet had to plate on wire a femur in a recent case, and this I ascribe to using the Thomas splint.

Leg.

Fractures of the lower portion of the tibia or fibula, and fractures through the ankle joint, I treat in a skeleton splint, such as I have illustrated (Fig. 3 a). It allows of easy access to the wound, and can without difficulty be modified to suit a special case. Fortunately, in gunshot wounds, the spiral fracture is rare, and, generally speaking, one bole remains unbroken. The treatment, therefore, of fractures of the leg does not present so much difficulty as that of the thigh. For transport, however, and for general comfort, the splint should immobilize the knee (Fig. 3 b).

FRACTURES OF THE UPPER LIMB.

Arm.

Fractures through the shoulder-joint and through the surgical neck of the humerus require no splints. The elbow should be slung at right angles and fixed by a broad bandage to the side. The dressings would probably replace the usual pad in the axilla, which should never be bulky. Shoulder shields are unnecessary and cumbrous.

The patient, where practicable, should be treated in the upright position and should have his head and shoulders well propped at night.

Where ankylosis is to be expected after a bad smash and suppuration of the shoulder and opportunity is afforded for continuous treatment, the arm should be kept abducted slightly forward, and slightly rotated inwards (Fig. 4).

This assures a much-extended range of movement at a very useful radius, such range of movement being brought about by the action of the scapula. This position need not be adopted if the patient has to be transported, as it can be established after the arrival home. Fractures through the elbow or immediately above the condyles are best treated without splints. If possible, the arm should be kept flexed well above a right angle.

Suppurating cases in the adult will not admit of the very acute flexion which we insist upon in the case of children. If, for a rare reason, a splint has to be applied, the internal wooden angular splint must be avoided because it is always clumsy and often causes deformity, and a splint as illustrated (Fig. 5 a and b) used.

Fractures of the middle and lower middle portions of the shaft of the humerus, where dressings have to be frequently changed, require very gentle handling, and I illustrate two splints which may be found very useful.

One is a modified Thomas knee splint used to maintain extension in the abducted position, the patient being recumbent (Fig. 6 a and b). The other is a modified Thomas humerus extension splint (Fig. 7 a, b, and c), to be used when the patient can walk about or sit up in bed. Either splint permits easy dressing and maintains adequate fixation.

As so much destruction of bone may be produced by modern shrapnel, and even by rifle bullet, great care must be taken to prevent over-extension, otherwise non-union will ensue.

Forearm.

The chief disability to be feared in fractures of the shafts of the bones of the forearm is inability to supinate the forearm completely. The trouble usually arises where both bones are broken, but it may occur where the radius alone is involved. We must remember that the whole length of the posterior border of the ulna is subcutaneous and is practically straight. On this straight ulna the curved radius rotates like the handle of a bucket. We must therefore attend to two points. First, we must keep the ulna straight; secondly, we must not interfere with the natural curve of the radius. That is to say, there must be no lateral pressure of bandage or splint on the middle of the shaft of the radius. In dealing, therefore, with these fractures, whether one or both bones be broken, the position of supination should invariably be maintained (Fig. 8). This is even more important in septic compound fractures than where no complication exists.

Neglect of this important point will often result in a locking of the bones in pronation. We must remember that in nearly all neglected fractures of the forearm, supination and not pronation is defective.

Wrist and Hand.

I have seen several cases of gunshot wounds through the Wrist, and they have been mostly treated with the hand in line with the forearm-that is, midway between palmar and dorsiflexion. This is fatal to a useful joint.

In order that the fingers may maintain their grasping power, all injuries of the wrist-joint should be treated in the dorsiflexed position, as shown in the illustration (Fig. 9 a, b, and c). Fractures of the hand may be immobilized as shown (Fig. 10 a, b, and c).

RETENTION OF LOOSE PIECES OF BONE.

I do not intend to deal with the surgical considerations involved in the treatment of the suppurating wound.

Many distinguished surgeons are devoting themselves to this problem. It may be well, however, to offer a word of warning against the destruction of loose pieces of bone removed from the wound. If quite loose they can be taken out, cleaned, and replaced. Even in the presence of pus telly may unite. Suppurative compound fractures unite well in time by giving them a common source of failure is due to the removal of bone.

PREPARATION OF SPLINTS.

The appliances which I have described can be obtained from

F. H. Critchley, 21, Great George Square, Liverpool. and for the convenience of surgeons at the front I append the measurements required when a splint is ordered.

Abduction Frame (Fig. 1 a and 1b).-Give measurements from nipple to external malleolus, and state left or right. For an uninterrupted splint-site of wound measured from nipple.

Bed Knee Splint (Fig. 2 ().-From fork to heel, also circumference of thigh at fork.

Long foot Splint (Fig. 3 a).-Length of foot, also heel to knee.

Short Hand Splint (Fig. 9a).-From palmar flexure of wrist to below metacarpo-phalangeal range, usually 21 in.

Long Hand Splint (Fig. 10 at).-Same as short, but to finger ends.

Extension Splint oar r)Ar (Fig. 6 a).-Circumference of arm at junction of shoulder an(d from axilla to fingertips.

Angular Elbow Splint (Fig. 5 a).-Wrist to olecranon, and olecranon to tip of shoulder.

Hunters Extension Splint (Fig. 7 a).-Wrist to olecranon, olecranon to axilla, and circumference of arm round shoulder.

Frequently the unaffected limb can be measured to ensure correct length, etc.

-

Fig. 1a. Left abduction frames with strapping extensions, wadding, and bandages used in application.

-

Fig. 1b. Convenience of abduction frame for transport.

-

Fig. 1c. Abduction frame applied.

-

Fig. 1d. Modified abduction frame for pelvic wound.

-

Fig. 2a. Thomas's knee splint, with strapping extension, local-splints, wadding, and bandages used in application

-

Fig. 2b. Strapping' extensions applied to leg. Bandage suspension slings to splint to support limb.

-

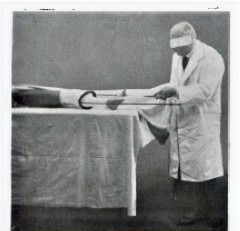

Fig. 2c. Introducing limb through ring of knee splint.

-

Fig. 2d. Knee splint in position, traction applied

-

Fig. 2e. Sheet iron splints moulded by hand for various uses.

-

Fig. 2f. Application of local splints.

-

Fig. 2g. Thomas's knee splints applied.

-

Fig. 3a. Skeleton splint for injuries near the ankle-joint.

-

Fig. 3b. Skeleton splint applied.

-

Fig. 4. Position to be maintained when ankylosis is expected.

-

Fig. 5a. Splint immobilizing elbow-joint but allowing access to it.

-

Fig. 5b. Elbow splint applied.

-

Fig. 6a. Modified Thomas splint to secure extension of arm. Note flattened face of ring

-

Fig. 6b. Extension arm splint applied.

-

Fig. 7a. Modified Thomas's humerus extension splint. Fig. 7 b.-With supporting bands in position.

-

Fig, 7c. Applied

-

Fig. 8. Securing supination in fractured forearm. Fig. 9 a.-Dorsiflexed wrist splint to secure good grasp.

-

Fig. 9b. Dorsiflexed wrist splint applied.

-

Fig. 9c. Dorsiflexed wrist splint applied,

-

Fig. 10a.Long dorsiflexed splint for wounds of hand.

Fig. 10b.Applied.

Fig. 10c.Applied

bottom of page