top of page

PRIVATE FRANK NOLAN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNEY THE GREAT WAR MEDICAL SERVICES 1 MEDICAL SERVICES 2 AMBULANCE TRAIN MILITARY HOSPITALS

WAR AND MEDICINE WHEN THEY SOUND THE LAST ALL CLEAR GROUP CAPTAIN DOUGLAS BADER GROUP CAPTAIN DOUGLAS BADER CBE DSO '

THE MEDICAL MEMORIES ROADSHOW

‘To understand where we are today

We have to know where we have come from’

SOURCE: - STORY OF THE GREAT WAR - BASED ON OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS - MEDICAL SERVICES - SURGERY OF THE WAR - VOL. I

Major-General Sir W. G. Macpherson, k.c.m.g., c.b., ll.d.,

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CASUALTY CLEARING STATIONS

AND FRONT-LINE SURGERY IN FRANCE.

THE Casualty Clearing Station was the development of a unit which was created in 1907 under the name of Clearing Hospital," and retained the latter name until January 1915. This unit had not existed in any previous war in which Great Britain was engaged. It was formed as a link between the field ambulance, which was organized after the South African War by combining the old bearer companies and field hospitals into one medical unit, and the lines of communication. It was intended for the temporary reception and care of sick and wounded pending and during evacuation from the front, and its functions were similar to those of the tent division of a field ambulance but on a larger scale.

The staff of a casualty clearing station consisted of a commanding officer, a quartermaster, six medical officers, and 77 N.C.O.'s and other ranks. No scale of transport was laid down for the units in the 1914 mobilization tables, but a footnote explained that if transport was required it would be furnished under orders of the Inspector-General of Communications. It was calculated that 17 general service wagons or eight 3-ton motor lorries were necessary for transport when the unit was ordered to move by road. Each unit carried 210 stretchers, 200 paillasse cases, 200 bolster cases,

480 sheets, 50 feather pillows, 400 blankets, and sufficient cooking and feeding utensils, medical stores and comforts, and tents for 200 patients, but no bedsteads or mattresses. The surgical equipment was small and included one small operating tent and one operating table. Each unit was provided with a few wooden splints, all of which were too slender to be of much service, and also with some yards of metal splinting material from which it was intended that other splints should be

improvised as occasion required. This material was called " aluminium splinting." But the reason of clearing hospitals being supplied on mobilization with this comparatively small equipment was because, being at or in the vicinity of railhead, additional equipment and stores could be more readily obtained from the base than in the case of divisional medical units, and it was also intended that use should be made of local resources.

Before the war, it was an essential part of the scheme for the treatment of the seriously sick and wounded that men should not be retained for treatment in the front-line units, where their presence might create difficulties and might interfere with the movements of the army. The prime duty of the

casualty clearing stations was therefore to arrange for the satisfactory evacuation of the wounded and sick rather than for their active treatment.

In the earliest days of the war in France the casualty clearing stations Were not in a position to take any great part in either treating or evacuating sick or wounded. At the time of the fighting at Mons and Le Cateau most of them were still packed up and on the railway, and it was not until the battle of the Aisne, in September, that they got to work. After this battle, when the army moved northward, the casualty clearing stations were able to unpack their stores and to make the best use of their equipment, so that they may be considered to have really embarked on their career during the

fighting which extended from Bethune to Ypres. It is interesting to note their positions with relation to the fighting line and the railways. No. 1 was at St. Omer, No. 2 at Bailleul, No. 3 at Ypres, No. 4 at Poperinghe, No. 5 at Hazebrouck, and No. 6 at Bethune. Both Bethune and Ypres were close to the

fighting line. Bailleul was about seven miles behind it ; Poperinghe about seven miles behind Ypres; while Hazebrouck was over fifteen miles from the front, and St. Omer about twenty-five miles.

All these casualty clearing stations were in buildings, and did not at that time use their tents to any extent, but already they had begun to expand and to take in far more than the 200 for which they were equipped. Thus, at Bethune, the casualty clearing station occupied a very large school for girls, and accommodated more than 600 wounded men while at St. Omer, the big Jesuit College of St. Joseph housed a similar number, and subsequently many more. All the other units also were forced to expand into neighbouring buildings, so that at Poperinghe No. 4 Casualty Clearing Station spread over three separate buildings, and No. 2 Casualty Clearing Station at Bailleul over two. This expansion meant a great strain on the staffs of only seven medical officers, and, combined with the

large numbers of the wounded, quite prevented any surgery being done except in an infinitely small percentage of the total number admitted ; but, small though it was, it was sufficient to show that a front-line hospital might be of very great value in supplementing the work of the field ambulances, and the experience of all the earlier months of the war convinced the surgeons that much more surgery was badly needed at the front.

The First Battle of Ypres cost in wounded alone about 13,000 men, and almost all of these depended on the general hospitals on the lines of communication for adequate surgical treatment,

whilst very many of them had to be sent at once to England, because of insufficient accommodation on the lines of communication in France. The reason for this was that the sudden move from the Aisne to the Ypres region had made it very difficult to send patients quickly to the hospitals in Paris or Rouen, and want of time had prevented the creation of large enough hospitals at Boulogne or Calais.

It must next be noted that efficient evacuation and treatment by casualty clearing stations were necessarily dependent upon the transport of wounded from the battle-field. When the fighting was transferred to the Aisne, and the line became stabilized, evacuation by train was less difficult, although extremely slow.

Motor ambulance cars were employed for the first time in bringing back wounded to railhead on the 20th September 1914, and the first organized motor ambulance convoy was formed on the Aisne at the end of September from ambulance cars sent out by the War Office early in the month.

Subsequently other convoys were organized and were at work on the Flanders front after the Expeditionary Force moved there from the Aisne. Thus, on 13th October, wounded, to the number of about 400, from the fighting around Meteren and the Mont des Cats were taken by motor ambulance cars to No. 1 Casualty Clearing Station at St. Omer. At about the same time other motor ambulance cars were bringing the wounded into No. 6 Casualty Clearing Station at Bethune from the area of Festubert, Aubers and Estaires. The numbers passing through the casualty clearing stations during the last week of October were very great, and without the motor ambulance convoys they could not have been brought in so rapidly from the field ambulances. On some days more than a thousand were admitted to a single casualty clearing station, so that all that the small staff could do was to dress the wounds and put the patients into trains as quickly as possible, while matters

were made still more difficult by the shelling of Ypres and the consequent removal of No. 3 Casualty Clearing Station from the town. A few days later No. 6 Casualty Clearing Station was shelled in Bethune and had also to retire.

It was during November 1914, when the German attack had been held up and defeated, that the opportunity came for improving the buildings occupied by the various casualty clearing stations. At the same time two very important changes took place, namely, the appointment of a few nursing

sisters and the supply of a small number of bedsteads and bedding. These were not only valuable additions in themselves, but they showed clearly the alteration of the original policy that wounded men were not to be retained for treatment at the front. This period, indeed, marked the first important development of a new arrangement by which, ultimately, the wounded were no longer retained in the field ambulances for operative treatment, but were sent on as quickly as possible

to the casualty clearing stations.

Early in January 1915, a most important development took place, in that a new and additional surgical equipment was supplied at this time to all casualty clearing stations, and this coincided with the formal approval of the Director-General of more operating work being systematically undertaken by the casualty clearing stations. The consequence was that during January and February large numbers of operations were performed at the front, and in quiet times when no heavy fighting was in progress a large proportion of the wounded were submitted to operation in the casualty clearing stations and were retained for some time before being entrained. Many of the worst cases were head wounds, the result of sniping, for the trenches afforded insufficient protection to both officers

and men. But while in quiet times the surgical work could be satisfactorily done to a great extent, as soon as the heavy fighting of Neuve Chapelle, Hill 60, the Second Battle of Ypres, and Festubert developed, the wounded had all to be evacuated to the lines of communication or even to England,

and the surgery of the front became again limited to the performance of only the most urgent operations and the application of dressings.

In June 1915, a further increase of equipment for casualty clearing stations was authorized and was quickly supplied,* so that during the rest of that summer the opportunities for good surgical work were greatly improved. At the Battle of Loos, however, on 25th September, the conditions again resulted in so large a number of wounded in proportion to the supply of casualty clearing stations and surgeons, that only a very small proportion of the wounded could be treated adequately at the front. In the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, in March, there were about 9,256 wounded, and during the months of April and May they amounted to approximately 67,041. The Loos fighting cost 38,161

wounded between 9 a.m. 25th September and 9 a.m. 15th October, and during the whole year 1915 the wounded totalled 206,113.

* "Bowlby Outfit No. 2."

It must be noted, however, that before the Battle of Loos was fought there had been two other important developments, namely, the erection of the first hutted and tented casualty clearing stations, and the creation of the first " Advanced Operating Centre." Nos. 10 and 17 Casualty Clearing Stations were erected in June and July 1915 at Remy Siding, near Poperinghe, and an advanced operating centre was established in preparation for the Battle of Loos in the 1st Army at Bac St. Maur, in the area of the 3rd Corps, and at Noeux les Mines in proximity to the battle front.

From this time onwards it was the policy of the Army Medical Service to erect casualty clearing stations on open ground, so situated as to be supplied with a railway siding for their own use, and with good road communication towards the front . Advanced operating centres were only erected when it was not possible to place casualty clearing stations sufficiently near the trench line, or when it seemed advisable to supplement the casualty clearing stations in anticipation of heavy fighting.

But, while the developments described above had been taking place, the personnel of the casualty clearing stations had remained unchanged and important reinforcements of medical officers and orderlies had not as yet been supplied until after the commencement of a battle. It must also be

remembered that it was only at the end of 1915 that the policy was finally adopted of not doing more operations than could be helped at field ambulances, and of consequently using the casualty clearing stations as front-line hospitals and transmitting wounded to them as quickly as possible.

The definite adoption of such a policy was necessarily followed by further changes in the casualty clearing stations. It had been found by experience that better results were obtained by getting wounded into the casualty clearing stations before any operations were undertaken, and for several reasons. In the first place, it was very advisable that serious cases should be in beds and well nursed ; and secondly, it was often much better to move a man before an operation than after it, for in many cases of bad abdominal, chest or head wounds movement directly after operation was very dangerous to life. Arrangements for sterilizing instruments, gowns, etc., were also much more difficult at field ambulances, and it was more difficult to obtain the necessary quietude and freedom

from disturbance. It may, therefore, be concluded that after the end of 1915 the bulk of the surgical work at the front was finally transferred from the field ambulances to the casualty clearing stations, and continued to be so during the rest of the war.

The necessary result of this transference of surgery was the appointment and training of suitable surgeons, and, whereas at first a single "surgical specialist" was allotted to each casualty clearing station, a "second surgeon" was now appointed as well. It was also very necessary that when any

surgeon showed great surgical ability and aptitude he should not be moved from his unit without sufficient cause, for the right sort of man would not only improve his own work by experience but would also help to train other members of the staff, and would organize and develop, in conjunction with his commanding officer, the whole surgical routine of his unit.

It thus happened that there grew up a body of young surgeons who, guided by the advice of the consulting surgeons of their respective armies, gradually developed a "surgery of the front,"based upon the principles of good civilian surgery ; and, as time went on, one heard less and less that the difficulties of the war conditions were sufficient to excuse poor technique or inadequate asepsis.

During the earlier part of 1916 many of the new casualty clearing stations were greatly enlarged, some of them being entirely hutted, but others partly in tents. As early as October 1915, it had been agreed that the small operating tent should be given up, and its place taken by a hut of 60 feet in length and 20 feet in width. This was subsequently the regulation supply on the entire front. It gave good room for four operating tables and their equipment. At the beginning of 1916 a " Memorandum on Wounds "was published by the War Office, and issued to all medical officers. It had been written by some of the consulting surgeons and physicians in France, on the instructions of the Director-

General of the British Expeditionary Force, and it formulated the conclusions as to some general principles of treatment agreed to in 1915.* The distribution of the memorandum was of * An enlarged edition was issued in 1917 under the title of "Injuries and Diseases of War." great assistance in establishing definite methods, and it enabled general instructions to be easily circulated at the front.

It was in accordance with this that the following memorandum, drawn up by the advising consulting surgeon for the front areas, was issued on the 27th April 1916, by the D.M.S. Fourth Army. It gives a good general idea of the methods which were then being adopted everywhere, and shows what

progress had been made at that time in the arrangements for treating wounded men.

'• TREATMENT OF WOUNDS."

"The attention of all R.A.M.C. of&cers is called to the memorandum—* Treatment of Injuries in War.'

All D.Ds.M.S., A.Ds.M.S. and Commanders of Medical Units should ensure that all medical officers serving under them (more especially those who have come from hoine) are in possession of the book, and that, as far as possible, the treatment advocated therein is carried out.

Special stress should be laid upon the following points :—

(1) Only operations of emergency should be performed in field ambulances,

but the' following exceptions should be noted :—

(a) Completely smashed limbs should be removed, and the patients

retained for at least a day before being sent to a casualty

clearing station.

[b) Haemorrhage should be arrested by ligature of bleeding vessels

whenever possible. If this is not possible, then plugging and

direct pressure on the wound itself should be resorted to ;

and patients should never be sent down with elastic tourniquets

on their limbs. Tourniquets have often caused gangrene,

and always cause very severe pain.

(2) Abdominal wounds require treatment at a casualty clearing station

as early as possible, and even if penetration is doubtful, should

be at once sent on by special motor ambulance. All wounds

of the loins and buttocks which are associated with abdominal

pains are probably penetrating wounds of the abdominal cavity,

and should be treated as such. Operations on the abdomen

are to be done at the casualty clearing stations, or at special

emergency hospitals.

{3) Chest wounds penetrating the lungs, and having large openings

admitting the free passage of blood and air, should be treated

by cleansing the wound, and plugging it with sterile gauze, and

applying rubber plaster so as to close it hermetically. If not so

treated, the patients often die of haemorrhage.

(4) In cases of fractures of the extremities, splints should always be

applied before the limb is bandaged. All wounds of joints should

also be splinted.

(5) The application of iodine to the skin, followed bj^ the use of cyanide

gauze, results in severe blistering, and this combination should be

avoided.

(6) Neither amputation wounds nor any other wounds should be

closed by sutures. They should be left completely open.

(7) All severe cases reciuiring early treatment at a casualty clearing

station should be at once sent there by a special motor ambulance

direct from field ambulances. They should not be kept waiting

for the regular convoys."

The preparations for the offensive on the Somme in July 1916 gave the first opportunity of arranging for surgery on a large scale in heavy fighting, and fourteen casualty clearing stations and one advanced operating centre with forty beds were supplied to the Fourth Army, which was the chief seat of attack, apart from the casualty clearing stations in the adjacent Third Army. Many of these casualty clearing stations were large enough to accommodate 1,000 patients, and on the night

of 1st July several of them accommodated twelve or thirteen hundred. In order to deal with the great numbers of wounded expected, the staff of medical officers of the casualty clearing stations had all been more than doubled before the battle began, and additional nursing sisters had also been supplied beforehand. All of these were further increased as soon as the numbers of wounded were realized. They were more numerous than in any previous battle, for on the first day about 14,400 men were admitted into 13 clearing stations of the Fourth Army, on the second day 13,806, and on the third day 8,793. The difficulties of adequately treating such large numbers were increased by

the fact that during the first twenty-four hours of the battle a sufficient number of ambulance trains had not come up to relieve the congestion in the casualty clearing stations. Yet many hundred operations were performed even when the stress was greatest, and in the four and a half months during which the battle lasted more than 30,000 operations were performed in the casualty clearing stations and the advanced operating centre of the Fourth and Fifth Armies alone. It should further

be noted that, in anticipation of much operating, very large numbers of additional surgical instruments and equipment of all sorts had been supplied, for without these the additional surgeons would have been of comparatively little help. The total number of wounded during the Battle of the Somme from 1st July to 17th November was approximately 318,408, of whom over 124,796 were treated in the month of July alone.

In the whole year 1916 the number of wounded was over 450,887. It has already been mentioned that the casualty clearing stations had been greatly enlarged for the Somme offensive, and it was at this time that certain general principles began to be evolved which ultimately resulted in the standardization of a definite system for the distribution and treatment of the wounded. In accordance with this, a casualty clearing station comprised :—

(1) A general admission tent or hut in which the necessary particulars were entered as each patient arrived.

(2) A tent for the dressing of walking patients.

(3) A tent for the dressing of lying-down patients.

(4) A pre-operation tent.

(5) A resuscitation tent.

(6) Tents where patients might be kept for treatment.

(7) Tents where patients for evacuation were placed.

In any casualty clearing station so planned, the patient was given hot drink of some kind on arrival, generally tea, and, if a walking case with a slight wound, he would be passed through the dressing tent straight to the evacuation area, and thence to the train. If an operation was advised his dirty clothes were removed in the pre-operation ward, and he was if possible dressed in clean pyjamas before being taken to the operating theatre. If he was suffering from shock or exposure he was

taken first to the resuscitation ward, and after operation he was either put in bed to be retained, or on a stretcher for evacuation.

X-ray Work in Casualty Clearing Stations.

As it had not been foreseen that much, if any, operation work would be done in casualty clearing stations, no X-ray outfits were originally supplied, but early in January 1915, mobile X-ray vehicles were allotted, one to the First and one to the Second Army. Later on, as the surgery of the front increased, additional mobile and fixed sets were supplied, and in 1917 many of the casualty clearing stations had their own apparatus. The value of the mobile X-ray vehicles varied greatly, and while

some of them were really mobile, others moved with difficulty or sometimes only moved at the expense of many breakages. As time went on, it became evident that the ideal was for each

casualty clearing station to be supplied with a lorry which carried all the X-ray apparatus arranged so that the power could be supplied from the lorry. Experience also showed that it was necessary to provide suitable "X-ray" huts instead of tents, as without huts the results obtained were never satisfactory. It was soon evident that X-rays were of the very greatest value at the front, and were if anything even more important there than at the base hospitals. In many cases their use obviated an exploratory operation, while in others they supplied the information without which no operation could

be performed. They undoubtedly constituted a very essential part of the equipment of all casualty clearing stations.

In some cases where there was a group of casualty clearing stations close to each other, a single power station was erected for the supply of them all. Thus at Tincourt in 1917 the X-rays of three casualty clearing stations were run from a single installation. But, as more and more demands were made for the use of X-rays at the front, it became evident that the officer in charge could not do the work unaided, and a skilled N.C.O. was added to the original staff. It also appeared that, just as it was necessary to supply surgical reinforcements for heavy fighting, it was necessary in addition to obtain the services of additional X-ray specialists. The supply of X-ray equipment and of special officers was never equal to the demand, for while the apparatus itself could be readily obtained, difficulties in supplying suitable engines remained to the very end of the war. The Grouping of Casualty Clearing Stations. As soon as the first grouped casualty clearing stations were established at Remy Siding in 1915, it became possible to arrange that they should be on duty "turn and turn about," and this meant that in so-called "quiet times" each was taking in during alternate periods of twenty-four hours. In this way each unit was able to get through the necessary work of treating the patients already admitted without being disturbed by the arrival of fresh wounded, and the whole staff had a period of rest from fresh admissions. From that time onwards the system of grouping two or more casualty clearing stations was adopted as a general principle, and by this arrangement it was easy to provide for a single railway siding or a single water supply for all the casualty clearing stations of any one group.

This was a saving of great importance. During heavy fighting the group system was also of great

practical value in another way, for it was then arranged that each casualty clearing station of a group should take in wounded, not for a certain fixed period but up to a certain number, and when this number was reached the motor ambulances arriving with wounded were "switched off" to the next casualty clearing station, until it also had received the allotted number. This arrangement was first put into practice for groups in the Somme fighting in 1916,* but afterwards became universal. The number that should be taken in before "switching off" necessarily varied in proportion to the pressure and to the number of surgeons at work, but whereas at first as many as 400 were admitted before another casualty clearing station took on the work, the longer the war lasted the more the

numbers tended to be reduced, so that 150 or 200 became a standard, and one severe case was often by arrangement counted as the equivalent of two patients able to walk. It was also found that when large numbers of wounded were arriving at the beginning of heavy fighting it was best to take in only 100 at first, or even less, for in this way the staffs of two or more casualty clearing stations got quickly to work instead of being kept waiting in idleness while the first casualty clearing station

on duty took in a large number.

*The system had actually been in practice in the First Army during the Battle of Loos in 1915, but before the grouping of casualty clearing stations.

The Work of Consulting Surgeons in Casualty Clearing Stations.

The development of the surgery of the casualty clearing stations was largely the work of the consulting surgeons at the front. In September 1914, two consulting surgeons were sent to France, and after the middle of October one of them. Sir George Makins, remained at Boulogne and the other. Sir Anthony Bowlby, began to visit the casualty clearing stations. It was not until May 1915, when the British Expeditionary Force had been divided into two armies, that a second consultant

was appointed to the front, but from that time onwards a consulting surgeon was appointed to each of the armies, and each of these held the rank of Colonel A.M.S. or, later on, of Surgeon-General.

Early in 1916 the Director-General in France decided that in order to co-ordinate the surgical work of the four armies now in the field, it had become advisable to have an additional consulting surgeon, and Sir Anthony Bowlby was appointed with the title of "Advising Consulting Surgeon, British Armies in France," and was thenceforth on the staff of the Director-General, with the rank of Surgeon-General.*

The work of the consulting surgeon at the front underwent very great changes as the war progressed. At first he was entirely utilized for the purpose of giving advice on certain wounded men or of doing an operation, and he visited the casualty clearing stations in order to see patients for whom his opinion was sought. Subsequently he also made suggestions on the equipment of the casualty clearing stations, and his advice was invited on various methods of wound treatment. At this period, however, it was no part of his duties to make arrangements for the surgical treatment of large numbers of wounded, nor was he consulted on the surgical arrangements for proposed offensives

* Sir George Makins was at the same time appointed "Advising Consulting Surgeon for the Lines of Communications " also with the rank of Surgeon-General.

His responsibilities were limited to giving professional advice. It was not until the Somme offensive was in preparation in 1916 that authority was given to the advising consulting surgeon to arrange with the D.M.S. of the Fourth Army for the necessary preparations to be made for surgical operations to be done in the casualty clearing stations on a large scale, and for the consequent increase of equipment and personnel. From that time onward the role of the consulting surgeon

was changed, and. he took his place on the staff of his Army D.M.S. and became responsible as an adviser in all arrangements for the surgical preparations in proposed offensives, for the surgical equipment and work in casualty clearing stations, and for the appointment of surgical specialists. As experience of front-line surgery grew, it became evident that good work required the co-operation of a responsible surgeon with the D.M.S. of each Army, and this in turn led to the Director-General appointing a committee composed of consultants and administrative officers, and also calling from time to time meetings of all the consulting physicians and surgeons. The consulting surgeon in each army also gave surgical instruction to the field ambulance personnel on such matters as the use of new splints, on new proposals for the treatment of shock, and on the various methods of intravenous

infusion.

It was the duty of the advising consulting surgeon to visit all casualty clearing stations and to co-ordinate the surgical work of all the different armies, to supply information of new methods of treatment, and to bring to the notice of the Director-General any surgical matter of which he ought to

be informed. He also advised on the appointments of surgical specialists to the casualty clearing stations, and as to the composition of the "surgical teams" which as occasion arose were sent as reinforcements, either from one army to another, or from the lines of communication units to the front.

The Battle of the Somme, in 1916, may be said to have fully justified all that had been agreed upon with regard to the necessity of good front-line surgery and the early operative treatment of the wounded man. It was, however, very evident that as yet only a beginning had been made, and that much more was required. Consequently, on 28th February 1917, an important consultation took place between the Director-General and the consulting surgeons of the front, to consider a memorandum by the advising consulting surgeon on the " Treatment of Wounds at the Casualty Clearing Stations," and it was decided—

(1) That early operation on wounds requiring it should be done at the casualty clearing stations whenever possible.

(2) That for heavy fighting the staffs of casualty clearing stations should be reinforced to a minimum of fourteen medical officers and fifteen nurses.

(3) That when surgeons were sent from one casualty clearing station to another for reinforcement they should take with them, so as to constitute a "surgical team," an assistant, an anaesthetist, and a nursing sister of experience in operative work.

(4) That beds should be provided for at least 10 per cent. of the total accommodation in each casualty clearing station.

(5) That when only one group of casualty clearing stations in any army was heavily worked reinforcements of medical officers should be sent by the D.M.S., in motor ambulances from his other casualty clearing stations, even if for only a few hours,

(6) That gas and oxygen and suitable apparatus for its administration should be supplied in large quantities for anaesthetic purposes.

The above conclusions arrived at by this conference were of the greatest importance to the surgery of the front, and may be said to. mark an era in the development of military surgery in France, for they definitely approved in principle of the arrangements recently evolved during the Somme offensive, while they also permitted a further expansion of the casualty clearing stations by officially providing a percentage of beds and an increase in the staffs of medical officers and nursing sisters.

In addition to this, the initiation of the system of reinforcement by definite "surgical teams "

proved to be of the utmost importance to the further development of military surgery in the ensuing years of the war, and from this time onward the custom of reinforcements by surgical teams within each of the five armies, apart from those sent by General Headquarters, was carried out at the discretion of the D.M.S. concerned. Consequently, whenever only a small proportion of the casualty

clearing stations of any army was heavily worked, it was very easy to send surgical teams from neighbouring casualty clearing stations by motor ambulance car within an hour or two.

The year 1917 opened with British attacks in the Somme region on a limited scale, but on 9th April the Battle of Vimy and Arras resulted in heavy casualties in the First and Third Armies. The rush of wounded had been fully anticipated and, in accordance with the arrangements already authorized, all the casualty clearing stations concerned were prepared with increased staffs and equipment of all kinds. The result was that a larger proportion of the wounded were passed through the operating theatres than ever before, and that an average of about 20 per cent, were operated upon in the casualty clearing stations, although between 9th April and 31st May the total wounded in the First, Third and Fifth Armies amounted to over 90,000, of whom over 17,000 were treated in the first three days of the battle. The results of this early surgery were shown at the general hospitals by a great diminution in the occurrence of gas gangrene, sepsis and secondary haemorrhage, and a general improvement in the well-being of the patients.

On 7th June the Battle of Messines was fought by the Second Army, and here, owing to the more limited objective, a larger proportion of casualty clearing stations was available and also larger staffs. On the first day 10,434 wounded were treated in eleven casualty clearing stations and one small advanced operating centre, and in three days a total of 16,238 wounded passed through the same units.* Over 2,400 of these were operated upon at once, with the result that the general hospitals reported only one-half per cent, of gas gangrene, very few amputations, and a very low death-rate. At the end of July Hill 70 at Loos was captured by the Canadians, and the consulting surgeon of the First Army reported that of the 4,000 wounded 20 per cent, were operated upon by thirty surgical teams utilizing twenty-three operating tables, and he compared this with 13,910 wounded on the first day of the Battle of Loos in September 1915, when there were only sixteen teams and sixteen tables. Preparations were begun early in anticipation of the fighting in the Ypres Salient, and in view of the experience gained at Arras and Messines, and of the unanimous reports of the greatly improved conditions of the wounded in units on the lines of communication, the advising consulting surgeon at General Headquarters proposed that—

* The actual number of wounded in all divisions of the Second Army was considerably higher, namely, 17,404, with 1,386 of the enemy in addition.

(1) Each casualty clearing station should provide arrangements for eight operating tables, instead of four as previously.

(2) Six surgical teams should be supplied to each casualty clearing station, and should each include an orderly used to operating theatre work.

(3) Extra medical officers should be supplied to bring the total medical officers of each casualty clearing station up to a minimum of twenty-four.

(4) Twenty additional orderlies should be allotted to each casualty clearing station, as well as additional stretcher bearers.

(5) The number of nursing sisters should be increased to twenty-five.

(6) Each casualty clearing station should be supplied with additional equipment of surgical instruments, operating tables, gowns, towels and other articles in proportion to the increase of the staff and according to schedules supplied for the purpose.

All this was agreed to, but as it was not possible to supply enough surgical teams from the casualty clearing stations of other armies alone, thirty-two teams were drawn from the general and stationary hospitals. It must also be noted that for the first time a number of surgeons from the United States and from the British Dominions were included in these teams. The supply of all these surgeons by the lines of communication was only made possible by the fact that the more operating work was done at the front the less there was to do at the base. The pendulum had now swung so far over that not only were operations not confined to the general hospitals as in early days, but far more were performed in the casualty clearing stations than on the lines of communication. At the beginning of the battle most of the fighting was done by the Fifth Army, but in the later stages the Second Army took the chief part. The attack began on 31st July, and from that date to 13th November 1917, the total wounded in the Third Battle of Ypres were :—

Second Army. Fifth Army.

August .. 5,631 .. 47,704

September 26,658 .. 22,504

October 48,212 .. 29,592

November 13,216 .. 3,600

Total .. .. 93,717 .. 103.400

Grand Total 197,117.

In the Fifth Army the casualty clearing stations dealt with 16,088 wounded in the first two days of the fight, and in the first three days 3,091 wounded were operated upon out of a total of 15,430 men. The percentage of operations to total wounded was 10-5 per cent, on the first day, 20-5 per cent, on

the second day, and 30-0 per cent, on the third day. The reports from the Second Army were much the same, and for the two armies together, during the whole period of three and a half months ending on 16th November, in all 61,225 operations were performed on 199,664 patients, t.g., more than 30 per cent, of the wounded passed through the operating theatres, with the result that comparatively few operations required to be performed at the general hospitals. The latter also reported that there was a welcome absence of surgical complications and a very low death-rate. The condition of the wounded from a battle of the same magnitude had never been so good.

The heavy fighting of 1917 terminated with the attack and counter-attack of Cambrai in the Third Army area in the last ten days of November, but, owing to rapid reinforcements from casualty clearing stations in the neighbourhood, the casualty clearing stations of the Third Army were well able to deal thoroughly with 25,000 casualties in ten days, notwithstanding the surprise of the German attack on 30th November. During 1917, the casualty clearing station work had

developed out of all proportion as compared with previous periods, and it will be seen later that in the last year of the war, 1918, it was not found possible to increase the surgical staffs further, because the whole front was simultaneously so much engaged at that period that such large staffs as those employed during the Third Battle of Ypres could not be supplied. It was, however, during the year 1917 that very many important surgical improvements were so established that in 1918 they had become generally adopted. Wounds which had formerly been merely opened and drained were now submitted to careful operation and excision. Some of them were being treated by the Carrel method of irrigation, but in an increasing number of cases they were closed by "primary" or "secondary" suture, as described on p. 244. The surgery of various special regions had been very greatly improved, so that operations on the abdomen, which were performed without great success in 1915, and by only a few surgeons, were now performed everywhere with gratifying results. Wounds of the lung were subjected to surgical treatment in many cases, and operations

for injuries of the head gave a much lower death-rate. Wounds of the joints, and especially of the knee, were carefully closed after excision of damaged tissues, and drainage of them was never employed where it could possibly be avoided. The administration of anaesthetics had developed the use of the "Shipway" warm ether apparatus, and gas and oxygen had proved so invaluable in cases of shock that, where it could be obtained, it was always employed in preference to all other anaesthetics.

At this time also the nursing sisters were trained in the administration of anaesthetics, because the shortage of medical officers had gravely increased. The experiment was a complete success, and more than a hundred medical officers were freed for other duties. During the fighting in the Ypres salient transfusion of blood was first employed on a large scale, and proved of the greatest value. It was given either direct through a paraffin-coated glass receiver, or else mixed with a "citrate solution," and before the end of 1917 the methods of transfusion and the classification of donors were standardized in every casualty clearing station, with the consequent saving of many

lives. During 1917 also much more attention had been paid to the treatment of shock, and in every casualty clearing station a special hut or tent was provided where arrangements were made for warming such patients, for administering rectal injections, or for transfusing blood. In addition to all these changes, the careful splinting of fractures had been greatly developed. It was at the end of

1915 that the " Thomas' knee splint" began to be used for a few cases of fracture of the femur, but it was not until the Battle of the Somme in 1916 that it came into general use during heavy fighting. In anticipation of this battle it had been supplied in large numbers to all the casualty clearing stations, and during the progress of the battles its use was taught to the field ambulances also by the consulting surgeons of the armies engaged. Its value was immensely increased by the invention in 1915 in the First Army of the "Stretcher Suspension Bar," which enabled the limb to be comfortably slung during the transport of the patient. And in 1917, before the British attacks began in April, the use of the Thomas' splint and the suspension bar had been demonstrated by the consulting

surgeons of all armies throughout the field ambulances, so that as the year progressed this method of splinting was carried as far forward as the regimental aid posts. Greatly improved splints of various kinds for the upper extremity had also been provided in large numbers, and it had become the custom to put up all fractured limbs in suitable splints before the patient was removed from the battle area, with the result that the condition of patients on arrival at the casualty clearing station

was very greatly improved. In the large majority of these cases there was no such shock as had always been the case when smashed limbs had been only imperfectly immobilized during transport by road.

As the natural result of all these improvements, the beginning of the last year of the war found the casualty clearing stations in every way better able to look after the wounded, and this was not only because there were now so many experienced surgeons but because there had been an advance in

surgical methods and equipment. The experience gained by the commanding officers also was of the greatest value in the invention of ingenious methods of utilizing huts and tents to the greatest advantage. The methods of pitching the latter quickly, and so as to make convenient wards and dressing rooms, had undergone great improvements ; the supplies from ordnance stores and from the Red Cross depots gave an infinitely greater amount of gowns, towels, gloves and so on, for the surgeons and nurses, while the selection of suitable N.C.O.'s and orderlies added to the experience of many battles had resulted in more rapid methods of recording particulars and of dealing with blankets, stretchers and motor ambulances than in former periods. Finally, but most important, it was now recognized that for heavy fighting it was essential that orderlies should be supplemented by from 50 to 100 stretcher bearers, and it had also been reiterated in many reports that stretcher carrying was very heavy work for which men of low category were of little value. It must also be noted that the whole motor ambulance transport had become most efficient. The transport was

really the pivot on which the whole surgery of the front turned, for unless the wounded could be rapidly evacuated from the field ambulances the casualty clearing station surgeons could not get

to work. The original custom of collecting large numbers of wounded in field ambulances and then sending them down en masse had long been given up, and every single man urgently requiring treatment at a casualty clearing station was brought direct to the latter in a special car from the advanced dressing station of the field ambulance. The cars were now often heated by warm air from the exhaust of the engine, and plenty of hot-water bottles and blankets were to be obtained.

The year 1917 had again been a costly one, for the total wounded amounted to 495,000. Yet in spite of the great numbers there was no doubt that the wounded men had been very much better cared for and treated than in the previous years of the war.

Before considering the closing stages of the war it will be convenient to allude briefly to the pathological laboratories of the front. In each of the five armies laboratories for pathological work were instituted, and many of them were attached to the casualty clearing station groups. As a result of this^ not only was it easy to obtain the pathological reports required for the treatment of individual cases in the casualty clearing stations, but in quiet times very valuable research work was carried on, and much of what was learnt of gas gangrene and of shock was the direct consequence of the activities of these units. Occasional meetings of medical officers at the front began to be held at the end of 1915, but it was only at the end of 1916 that they became of much importance. They took place at various casualty clearing stations, and were encouraged and organized by the Directors of Medical Services and the consulting surgeons. Not only did they help to spread in each army a

knowledge of recent developments in any one casualty clearing station, but they also provided an opportunity for discussing the work done in other armies, or in the general hospitals. In this way the knowledge of improved methods or technique, or of new bacteriological arid other advances, was rapidly spread to the great advantage of the whole service.

At the end of 1917 also arrangements were made for the interchange of surgeons between the casualty clearing stations and the general hospitals. Until this was done it was often difficult for the surgeons at the front to learn by experience what happened to the patients evacuated by them to the lines of communication, and on the other hand a visit to the front for several weeks showed the surgeon who had only worked at a general hospital the difficulties due to delay in rescuing

wounded men, and to the rush of wounded into the casualty clearing stations when heavy fighting was in progress. Such experience was very shortly to prove valuable. Mention must here be made of the creation in the First Army of a medical school attached to one of its casualty clearing stations, where a course lasting fourteen days was instituted. Its object was to instruct men who had not yet

had experience of work in casualty clearing stations in the recent developments of military surgery, and to show what might be done at aid posts or field ambulances. These courses were especially helpful to young medical officers who had only recently arrived from England, and had perhaps only lately become qualified to practice. They learnt especially the methods of resuscitating badly injured men and also the application and uses of new varieties of the splints used at the front. There were also lectures on military law, map-reading, and the common diseases of the horse. The success of this school resulted in the creation in the spring of 1918 of a school for the whole expeditionary force, and it was evident that, had the war continued, this would have been of great service.

During the winter of 1917-18 the operating theatres of all the lines of communication hospitals were, on the recommendation of the advising consulting surgeon, fitted with extra operating tables and instruments in anticipation of an enemy attack and of difficulties arising in the operation work at the

front. In September 1916 instructions had been issued by the D.G.M.S. to make arrangements for the greater mobility of sections of the casualty clearing stations, and orders were given for schedules to be prepared showing what material could be carried on nine 3-ton lorries. Arrangements were also made to echelon the casualty clearing stations, and some of the most

advanced of these were withdrawn in anticipation of a German attack. In spite of these precautions, however, the enemy advance of 21st March rapidly endangered the casualty clearing stations of the Fifth and Third Armies, and although they were able to do very valuable work for several days, they had then to be evacuated, and most of their equipment was sacrificed although no patients were left behind. As they withdrew they gradually reverted to a large extent to their original role of clearing the field ambulances, and entraining centres were formed at places like Villers-Bretonneux and behind Albert and Amiens, where dressings were applied and limbs were splinted, the patients being evacuated both by road and rail to the general hospitals in the rear for operative work. Further north, in the areas of the First and Second Armies, where the attack did not develop so quickly, the casualty clearing stations were withdrawn successfully and reestablished farther back. As a result of this, they were able to deal with the wounded with the same efficiency as in 1917, although the work had to be done in tents for the most part.

Very efficient operating theatres were also developed by the ingenious pitching of several marquees together, and from this time onward the proportion of tents to huts became very greatly increased. As an example of work in this period, it may be noted that the First Army had 12,865 wounded

between 9th April and 21st April, and that 23-5 per cent, of these were passed through the operating theatres of the casualty clearing stations before being evacuated. By the month of May the line had become again stabilized, and the front-line surgery had resumed its former routine. But, in view of probable British advances in the near future, more mobile operation and X-ray huts were designed, and a mobile operating theatre with its surgical equipment, which had been designed in the First Army, was now supplied to other armies also. It was constructed so as to be mounted on an Air Force trailer and could be hauled by any lorry. On 27th May the German armies attacked in the Chemin des Dames region, where six British divisions were attached to the French forces, and No. 37 Casualty Clearing Station was captured together with about 200 wounded men. The staff remained, and were permitted to continue in charge of their patients for the next two or three weeks. Six weeks later three casualty clearing stations were again in the French area, one at Sezanne, south of the Marne, one at Epernay, and one at Senlis. Their presence in these regions was called for because two British divisions were co-operating with the French near Villers Cotterets, and two others were between the Marne and the city of Rheims. The sites of these casualty clearing stations were settled by the French authorities, but they were at far too great a distance from the fighting line, with the result that it took so many hours to transport the wounded that an ambulance car could only make about two double journeys in twenty-four hours. Many of our wounded were, therefore, treated in the French hospitals, and several hundred more were taken to an American general hospital at Dijon.

The casualty clearing stations also had not been able to take nearly all their equipment with them because of difficulties in train transport, and the advanced depots of medical stores encountered

similar difficulty. The consequence was a shortage of essential splints, for the number of wounded admitted to British casualty clearing stations was over 5,000. The opening of the great British offensive on 8th August found the casualty clearing stations both fully staffed and well equipped, for all the loss of material and equipment due to the German attack of March had long since been made good and several units were already packed up and waiting to move forward with the advance. The proximity of the Amiens front to the general hospitals stationed at Abbeville and Rouen also permitted of many patients being evacuated to these areas who would ordinarily have been retained in the casualty clearing stations. The new arrangements making for increased mobility worked very well, and as early as 9th August two casualty clearing stations were pushed up and opened for work in the Asylum at Dury, and on the 10th two more in tents at Vecquemont. Between 8th and 12th August about 19,000 wounded were treated in the casualty clearing stations, and about 10 to 15 per cent, of these passed through the operating theatres. Nearly all the wounds were due to rifles and machine guns fired at longer ranges than had previously been used, and consequently the proportion of slight wounds was very much higher than in the case of shell injuries. It must also be noted that, as all the general hospitals on the lines of communication had been supplied with extra operation tables and instruments, they were able to do much more surgery than ever before. The result of this combined work at the casualty clearing stations and the general hospitals was most satisfactory and inquiries made on 13th August showed that of a total of 10,000 wounded admitted to the Treport, Abbeville and Rouen areas the mortality had been only one-half per cent., the amputation rate one-half per cent., and the incidence of gas gangrene one-quarter per cent.

August saw a rapid extension of the attack northwards, so that the casualty clearing stations of the Third Army became very busy. This was followed at the end of the month by an extension of activities to the First Army, with the result that in four weeks from 8th August over 103,000 wounded men had been treated in the casualty clearing stations. Both in August and September the casualty clearing stations were well able to keep touch with the advance, and early in the latter month they were across the Somme in the south. All huts except those for operation and X-rays had been left behind, and tents alone were in use. Only a very little time was now required to make ready for work on a new site. For example, on 18th September a casualty clearing station was moved up to Doignt near Peronne to be ready for heavy fighting. It arrived at 6 p.m., took in and treated more than 500 patients before noon next day, and within the week it again moved a few miles to another site. Similar instances occurred in other parts of the line. As a result of the British attacks of 27th, 28th and 29th September the Hindenburg line was broken, and the army advanced in October to the other side of the devastated area where towns and villages with good buildings were occupied.

Consequently, as at Caudry, the casualty clearing stations were housed in large factories and other industrial buildings, while farther north, at Douai and elsewhere, existing hospital buildings were taken over. In the wetter and colder weather these were a great advantage to the wounded men, of whom there was a total for the month of September of over 105,000.

The Fourth, Third and First Armies had severe fighting and sustained many casualties in the first fortnight of October, and on 14th October the Second Army in the Ypres region continued the offensive it had begun on 28th September, and three tented casualty clearing stations were established at Brielen, just behind Ypres, in readiness for work. Fortunately the wounded here were few as compared with previous attacks farther south, and amounted altogether to 1,166 in three days. Of these no fewer than 457 were passed through the operating theatres. The great majority were wounded by bullets, for the Germans had withdrawn most of their guns, and it was on this day that the last shell was fired into Ypres, almost exactly four years since the bombardment commenced. From this date till the end of the war difficulties increased daily, for the British armies were now faced with railways so destroyed as to be for the time irreparable, and with roads blown up at numerous places. The consequence was that there was so great a demand for lorries for the supplies of food and ammunition that the casualty clearing stations often could not be moved for want of transport, and as time went on the difficulties increased as the advancing troops left the railways farther and farther behind them, and as the lorries broke down from excessive work on very bad roads. Here and there, as at Carnieres, Daddizele and Roubaix, sections of casualty clearing stations were pushed forward to do the more urgent surgery, pending the supply of transport for the rest of the unit, but for the most part the wounded had to be brought back fifteen or twenty miles before a casualty clearing station was reached.

In addition to these difficulties large numbers of sick or wounded civilians, including many women and children, had to be taken in and cared for, whilst the occurrence of a severe epidemic of influenza and pneumonia caused dangerous illness in many thousands of soldiers who had to be evacuated to the general hospitals. The staffs of the casualty clearing stations and field ambulances also did not escape the prevailing epidemic, so that the work of all the front-line units became most difficult. Fortunately the numbers of wounded fell materially in the latter half of October, and at the same time shell wounds still caused only a minority of the casualties, so that the proportion of badly wounded men remained low. The total number of wounded passing through the casualty clearing

stations in the month of October reached over 88,000, but in spite of all the difficulties wounds did well, and the reports from the lines of communication showed that there was still a low rate of mortality and of wound complications. The total number of wounded treated in the casualty clearing

stations during the advance commencing on 8th August was nearly 312,000, and for the whole year 598,000. Method of Working a Casualty Clearing Station. It may be well to describe the way in which a casualty clearing station was working at the end of the war, so that a comparison may be made with its manner of working in May 1915. In 1918 the casualty clearing stations were grouped and housed in a series of lashed tents. Each took in one hundred and fifty wounded in action before switching off to another casualty clearing station. There was a large party of bearers, made up of men of low category or, possibly, convalescent patients, and the wounded man was lifted from the ambulance and taken into a long reception room made of five or six tents. Here he was seen by the receiving officer who separated the cases, the medical being sent to medical wards.

After the particulars had been taken by the clerks, the wounded man was carried to the dressing tent, where his wound, if slight, was dressed, and he was then taken to the evacuation ward, which was near the road. If more seriously wounded he was passed on to the pre-operation ward, where

his clothes were cut off, and he was cleansed, warmed and fed. If on arrival the condition of a patient was found too serious for operation, he was taken to the resuscitation ward, where a medical officer, a sister and orderlies attended to his revivification; he was rested, warmed, infused or transfused as might be necessary. By the end of the war the practice of transfusion had attained a high pitch of excellence, and the number of transfusions in a single unit very often reached a dozen

in a day. Next to the.resuscitation and pre-operation wards was the X-ray department, through which every man requiring X-ray examination passed before he was taken to the theatre ready for operation. In the operating theatre a great change from the early days had taken place. There were one or two theatres accommodating twelve tables arranged in pairs, each pair being divided from the other so as to give a little privacy. Two tables were provided for each team in order to prevent waste of time. After operation the man was carried out, and if his injury was comparatively slight he was placed in the evacuation ward which, as already stated, was somewhere near the road. If too ill to be evacuated, he was taken into the retention ward, which was situated in as quiet a place as possible at the back of the casualty clearing station ; there he was attended to by the nurses and medical officers.

It will therefore be seen that there was a definite route marked out for every man arriving in the casualty clearing station, and so well were arrangements carried out, that if a visitor entered when a convoy had ceased arriving he might stand in the centre and find it hard to believe that the place was working at fever heat day and night. Towards the end of the war the practice had arisen of separating the walking wounded from those who were more seriously injured. The idea was to make the working of the casualty clearing station, where seriously wounded were received, quieter and easier, for the walking wounded had a great tendency to stroll about the place to seek out friends and create a considerable amount of noise in talking to them. Two plans were adopted in fixing the site of these walking wounded casualty clearing stations. One plan was to push a casualty clearing station as far forward as possible and evacuate the wounded on temporary ambulance trains ; the

other was to carry the walking wounded back from the active area by a light railway. The following is a description of a walking wounded casualty clearing station which was established about 7 kilometres south of Arras, during the fighting in September 1918, when the Canadians broke the Queant-Drocourt line. The wounded arrived by lorry from the front or by an improvized train

from Queant. The lorries drew up in front of three huge reception rooms, each made of eight lashed tents, for it was necessary to get the walking wounded under cover and within some bounds. In each of these three reception rooms was a coffee-bar kept by the Y.M.C.A.

Fig. 1. - Sketch plan of Casualty Clearing Station for seriously wounded

Across each room, about two-thirds down, were tables at which the clerks sat. The men passed through spaces left between the tables and the particulars were recorded. When the man emerged from the big tent a duck-walk led to the dressing tent. This was a long room made of eight marquees ; down its centre was a series of tables with surgical material. When the man entered the dressing tent an orderly bared his chest, cleaned it, applied iodine and passed him on to another orderly, who gave him antitetanic serum.

Fig. 2.—Sketch plan of casualty clearing station for walking wounded.

A., A.T.S. team; B., fridge leading out of camp; C, Cook-house; CO..Commanding Officer's office ; DIS., Dispensary; DR., Dressing tent; D.T.,Dining tent ; E., Evacuation wards ; H., Hot-water boiler ; E.L., Electric light engine; K., Officers' mess kitchen; L., Latrines; M., Matron's office; O., Office; OFF., Officers' ward; P., Policeman; PK., Pack store; P.OP., Pre-Operation ward ; E.O., Evacuation officer ; POST OP., Cases for evacuation ; QM., Steward's stores, etc. ; R., Reception ; R.O., Recording office; SM., Sergeant-Major; TH., Theatre ; U., Urinal; W.C, Water-cart; W.T.. Water tanks; CL., Clerks.

The man then took one of the vacant places on the benches, where he was attended to by the sister and orderlies working under a medical officer. He passed out of the long tent and was conducted into another series of tents where there were stretchers on which he could lie down, or, if he

wished, he could go to a dining tent. When an ambulance train arrived the men were marshalled by non-commissioned officers and marched down to it. A pre-operation ward, a theatre and a post-operation ward were provided, for about 4 per cent, of wounded required operation and about 10 per

cent, of them became "lying cases" for one reason or another.

The Regional Incidence of Gunshot Wounds.

A table showing the incidence of wounds in trench warfare in 1915 is given on p. 28, but it must be kept in mind that in the fortnight during which these figures were collected the troops were in the trenches and there were no raids of any importance on the enemy lines. It will be seen that out

of a total of 3,285 the wounds were situated as follows, steel helmets being not yet in general use :—

Head, face and neck . , 761

Shoulder and back 360

Chest 167

Abdomen 100

Lower extremities, including buttocks 997

Upper extremities 614

Multiple . . 286

It should also be noted that only a little more than a quarter of the total wounds, namely, 897, were attributed to bullets, and there is no doubt that in attacks on enemy positions and in the open warfare of the latest stages of the war the proportion of wounds by bullets from rifles and machine-guns was very much higher than in the earlier stages. What was probably of greater importance was the relative incidence of "dangerous" wounds, for a wound of the " back " or the "buttock" might mean a wound of the lung or the abdomen, and a wound of the "thigh" or the " arm " might or might not be complicated by fracture of a bone or the opening of a large joint. What really interested the surgeon and was of vital importance was the percentage of wounded men demanding some special treatment, for on this depended the whole of the arrangements for surgical treatment in the casualty clearing stations. In the first place it was necessary to provide a sufficient number of splints for patients with fractured bones, and it was also advisable to be able to arrange for the treatment of wounds of the different viscera and to set apart certain beds for patients with wounds of the abdomen, head and other severe injuries. After some experience it became possible to forecast with sufficient accuracy the expected number of serious or dangerous wounds in any big attack, and a very simple rule enabled all arrangements to be made. This was called by Sir Anthony Bowlby the

" two per cent, rule," for out of every hundred cases certain wounds might each be expected to occur in 2 per cent, of the patients. The following table shows the distribution per cent, of serious

wounds and the number of splints required for fractures.

" The attack of to-day is the first in which our men have practically all worn the new steel helmets, and I, therefore, spent some time in investigating the effects of this form of protection

Officers and men alike spoke with the greatest enthusiasm of the helmets, which, they said, had protected them especially from the fire of trench-mortars and shrapnel. My own examination fully confirmed this, for nearly forty out of about the first 350 helmets examined showed evidence of

having been hit. In some the metal had been only excoriated. In others it had been definitely bulged in. In a few it had been perforated. One helmet showed three large bulges, each as big as the bowl of a small teaspoon, yet the man's head was unwounded. In others, the helmets had been torn

open by large shell fragments without the skull being injured."

There can be no doubt that if troops do not wear these helmets the incidence of dangerous head wounds will largely exceed 2 per cent.

Operations and Mortality in Casualty Clearing Stations.

The following tables illustrate some interesting points. Table III shows the mortality at a casualty clearing station, and it will be noted that the mortality is much higher in winter than in summer, due probably to the effects of cold.

In quiet periods in a casualty clearing station, medical officers put 50 per cent, of wounded on the operating table, and, to avoid dangerous operations at the base, had to operate on 25 per cent. As one surgical team does twelve operations in twelve hours, two surgical teams were required for every hundred wounded. Table IV shows the composition of ten surgical teams required to work a casualty clearing station taking in 500 wounded in twenty-four hours.

In the battle of Arras, April 1917, the figures are not complete but the percentage of wounded operated upon according to H. M. W. Gray was 24. Similarly in the battle of Amiens in August 1918, when the first advance took place, the percentage of operations is shown as 15 during a period of four days, although the number of wounded to which the percentage refers has not been given.

Table VI shows what was accomplished in the battle of Estaires, 9th April 1918. It will be noted how the percentage varied from day to day and how the casualty clearing station always strove after the 50 per cent, standard antiseptics should be adopted and, owing to this advocacy, a thorough trial was made in November 1914 of carbolic acid, either pure or in strong solutions, but no good results were obtained and its use was abandoned.

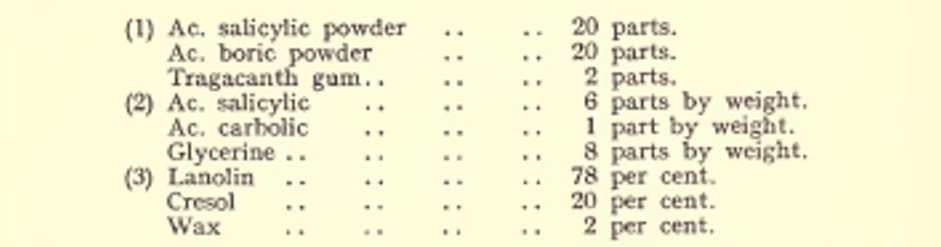

Borsal Powder and Cresol Paste.—In February 1915, Sir Watson Cheyne advocated the use of an antiseptic powder and an antiseptic paste. The first consisted of equal parts of powdered salicylic and boric acid and was named "Borsal."

The second was of three varieties :—

It was hoped that the paste, by giving off its antiseptic slowly, would thus act on the infecting agent continuously. A supply of these pastes and powders was, therefore, sent to France on 4th April 1915, and they were tested both by a surgeon, who had been instructed in their use in England by

Sir Watson Cheyne, and also by other surgeons selected for the purpose in France. The following document of instructions was supplied by Sir Watson Cheyne, and was distributed together with the antiseptic agents :—

" Directions for the use of Borsal Powder and Cresol Paste."

" In the case of a wound at the Front the first thing is, of course, to stay the bleeding as much as possible, and then to powder the whole surface thickly with the borsal powder. The cresol tube is then introduced into the wound and small quantities of the contents are squeezed into it in various directions, endeavouring as far as possible to leave small portions of the pacte scattered over the whole area of the wound, not more than 1 in. apart. Some of the paste should also be smeared over the skin around the wound, and after a final dusting with the borsal powder the emergency dressing is applied.

This can all be done quite quickly, and then the patient can wait till such time as the wound can be more thoroughly attended to. When the patient arrives at the advanced dressing station, the treatment depends on circumstances.

(1) If a large number of wounded have to be attended to, patients who have been treated in the above manner can wait, unless a good many hours have elapsed since the injury. In that case the orderlies should inject a little more paste into the wounds and powder them and apply a fresh

antiseptic dressing while the patient waits his turn. In the case of wounds which have not been treated, the orderlies should apply the powder and paste at once.

(2) If it is a large or complicated wound, e.g., a compound fracture, it will be well in the first instance to clean and disinfect the skin, preferably with 1 in 20 carbolic lotion, then wash out the wound with peroxide of hydrogen and 1 in 20 carbolic lotion, remove pieces of clothing or accessible pieces of shell, clip away any badly soiled tags of tissue and arrest the bleeding. The wound being dried and held open it can now be powdered with borsal and some cresol paste left in various parts of the wound. If it is widely open it may be well to put a few interrupted sutures in to bring the edges somewhat together and prevent the escape of the antiseptic, and finally apply antiseptic dressings.

(3) If it is not a large wound, if the clot seems solid and if it has been well powdered and plenty of paste introduced into it in the first instance, it is quite possible that sepsis may not occur and if that seems likely all that need be done would be to squeeze a little fresh paste and dust some borsal

powder over the surface and the skin around and apply a fresh antiseptic dressing. These wounds will probably not require further dressing till they arrive at the base hospital.

Subsequent Treatment at the Base.—Should the wound be free from sepsis or inflammation on arrival at the base hospital it should not be opened up or syringed or otherwise interfered with. Some fresh paste, diluted if necessary, may be applied over the surface and the skin, and a fresh antiseptic dressing put on. If, on the other hand, there are signs of sepsis, the wound must be opened up and drained and otherwise treated according to the experience of the surgeon."

These instructions were carried out in various parts of the front, and the patients so treated were, in some cases, retained for observation, and in others were sent at once to the general hospitals. Although the treatment was at first carried out with much enthusiasm, there was a general consensus of opinion that it was positively harmful, and the following report, dated 17th May 1915, on cases treated with cresol paste is typical of the opinions of practically all the surgeons who were asked to record their experiences :—

" At the present time there are in this hospital 28 cases which have been treated with cresol paste. Many more have been passed through recently but no record has been kept of their number or condition. So fax as my observations go, the results obtained have not been satisfactory. Some of the cases have obviously been anaesthetized, the damaged edges of the skin wounds excised, the openings enlarged, good drainage provided and the paste introduced. These have been on the whole satisfactory, but the results, if as good, are no better than in similar cases simply treated by

incision and free drainage. In cases which have been treated simply by external cleansing, injection

of paste, and the application of protective dressing, the use of the paste appears to have a harmful effect. In the cases of the latter group the wounds are commonly found plugged with a mass of coagulated blood and paste.

When the plug is removed a profuse discharge escapes, the tissues are greatly swollen and gas is not uncommonly present.

(1) The paste with the blood forms a dense putty-like mass which plugs the wound openings, dams up the secretions and by interfering with drainage pre-disposes to diffuse septic infiltration.

(2) The paste and blood coagulum adhere very closely to the tissues. It has been found to be very difficult to clean up wounds treated with the paste.

(3) There is often excoriation of skin edges and blistering of surrounding skin surface due apparently to the action of the paste.

(4) It does not appear that any useful effect has resulted from the use of the paste."

It only remains to add that the opinions of surgeons, both at the front and at the base, were unanimous, and the further use of both powder and paste was stopped.

Hypertonic Saline Solution.—The treatment of wounds by the use of a strong solution (60 grains to the ounce) of common salt was advocated by Sir Almroth Wright in 1914 and 1915. It was employed chiefly in the base hospitals and was never widely adopted in the front-line units. Its employment is

described more fully on p. 252, but its use was accompanied by much secondary haemorrhage and it was gradually abandoned in favour of better methods, and was practically not employed in the casualty clearing stations after 1915.

Various Antiseptics.—All kinds of solutions were employed to wash the wounds, and various powders, such as iodoform or boric acid, were used, but none of these agents prevented the wounds from suppurating or obviated the need of free drainage. Various aniline dyes in oily solutions were also employed but with no better results.

Carrel's Method of Wound Treatment is described in the sections dealing with wounds in the general hospitals.

Early Excision of Damaged Tissues.—The treatment of wounds by free excision at the casualty clearing stations was generally adopted as an alternative to the use of free incisions for drainage,

and after the year 1915 it became a common practice during quiet periods. It could not, however, be employed at that time during a battle because of the small size of the clearing stations and the scarcity of their surgical personnel, and it was not until the first battle of the Somme in 1916 that it began to be adopted at the front on a large scale. From that time on it was the regular practice, and was proved to be the most efficacious means for the prevention and arrest of gas gangrene. The earlier this treatment was carried out and the more thorough the removal of all torn muscle and foreign bodies, the more satisfactory were the results, and during the heavy fighting of the year 1917 the large majority of all the severe wounds were treated in the casualty clearing stations by this